The artist recalls his experiences studying with photographer and teacher Sid Grossman, one of the founding members of The Photo League. See also the essay “The Photo League.”

It was just after World War II that I had the unique opportunity to listen to Sid Grossman talk about photography. The year was 1948; I remember it as if it were yesterday.

A few years before I had joined a young, active trade union called Wholesale and Warehouse Union (Local 65). The group had become a center for progressive political action in the metropolitan area. Its members never tired of demonstrating for one cause or another. We wore our green Local 65 buttons proudly, as a badge of honor and camaraderie. There were dances on Saturday night, a theater group who performed humorous skits about strikes and the current political scene, and classes offered at the union headquarters, a large, dark, red brick building on Astor Place in Manhattan. (It was called “Tom Moony Hall” after a little-known labor leader. I remember it well because I had, in fact, been responsible for coming up with the name during a name-that-building contest.)

After returning from active combat, I was in a quandary about my future occupation. I had been trained as a printer, primarily as a hand typesetter and make-up man. By the time I was eighteen I was the foreman of a printing plant, but didn’t want to return to that. Several agencies that specialized in career counseling had recommended an artistic profession for me; one suggested that I would make a good music critic. Although I loved music, I scoffed at that advice. Who had ever heard of a music critic making a living? I had taken a sketch class in modeling, but I wanted something more dynamic and involving. I had recently bought a folding camera, a Kodak Monitor, similar to the one my brother, who was a photo enthusiast at the time, had.

I signed up for a photography course that was being given on Saturdays for ten weeks, one hour a week, at a dollar per session. It was taught by Sid Grossman. He sat at a table in front, raised on a wooden platform, facing about fifteen students, who sat in those school chair-desks with the wide, right-arm rests. (The number would dwindle down to eight by the last few sessions.) His position gave him an edge that seemed quite unnecessary, since we were all basically beginners. Moreover his attitude—arrogant and aggressive—was apparent from the very first class.

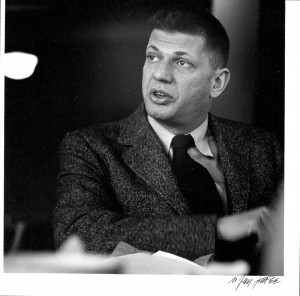

I would stare at Grossman as he entered the room each Saturday morning. About thirty years old, he had dark, short hair, which had once been cropped in a crew cut. He usually wore a wool tie and a dark blue or grey tweed sports jackets. I was amused that he wore his army shoes. I also wore mine on weekends, except the ones I wore were combat boots. He smoked incessantly, although it didn’t bother me at the time.

His appearance wasn’t particularly striking. But his personality was. If I could find some of those students who suffered through those classes with me, I’m sure they would agree that Sid Grossman did not seem to take kindly to our presence. He was almost contemptuous; each of us got a taste of his anger and hostility during the course. We were told to bring in our work for a class critique each week. If Sid didn’t care for a student’s photograph, he would tear the print and throw it at the culprit, demanding that he never bring in “such garbage” again. When one of the students confronted Grossman about his manner, he retorted, “I’ve been in photography a long time before you came here and I’ll be in it a long time after you’ve left it!”

When Sid vented his anger, I felt embarrassed and uncomfortable. Yet from the first moment he entered that bare classroom, I felt a kinship with Sid Grossman. He never intimidated me. I didn’t know what his politics were or anything about his personal life. He never even mentioned The Photo League, of which he was a founding member, to us. His genius was in expounding a philosophy of photography that was unique. I had never heard anyone speak on a subject with such depth and enthusiasm. I still recall a phrase he repeated several times: “The world is a picture.” This simple statement was a profound insight into the method and meaning of photography.

To Sid, photography was serious, not sacred. When a student would bemoan his loss of a photograph opportunity, Sid would simply tell him a story about the “fish that got away” and advise the student to take his camera and “go fishing” again. Sid intensely disliked phonies. He spoke with disdain about the salon photographer who would comb the Bowery for a likely subject. Once found, the photographer would lure the “bum” to his studio, dress him up, sit him before the camera with elaborate lighting, suddenly throw a glass of water in his face, and make an exposure. The result was a 16 x 20 soft-focus print, on pebble-finished paper, with a title such as “Old Salt.” I had seen work like this in photography magazines and was never impressed with it. Grossman helped me understand my instincts.

The class consisted mainly of Grossman’s lectures. There was very little discussion. I don’t recall him ever bringing in his own work or the work of other photographers. He never mentioned Walker Evans, Alfred Steglietz, or Atget. Not all the students did their own work [developing]. If I had technique problems, I would corner Sid after the class and he would usually answer my questions.

I was just beginning to photograph the kind of subjects and images that would later become my particular style, I was already developing film and contact printing my own work, because I had been disappointed by the commercial printing that the lab at the photo shop provided. I especially disliked the deckle edges that were the style then. Making my own contact prints, with a small Kodak frame and a small bulb as a light source, was a remarkable revelation. The negative, pressed under glass against the printing paper, was the best possible way to get the best print. Some negatives were printed again and again, until I got the print I was looking for.

At that time I lived in an unusual, two-story house on Logan Street, in the East New York section of Brooklyn. The house stood off the corner of Linden Boulevard. The area was undeveloped to the south of the boulevard, and, looking towards Jamaica Bay, all you could see was flat, empty terrain. It was an eerie sight. The house, surrounded by a cement wall embedded with glass, was built by an Italian architect, who also died in it. (According to local legend, he was killed and eaten by the dogs he owned!) Like other veterans, I had had trouble finding housing. I made up a flyer announcing the need for an apartment, and offered a reward of $25. The New York Post (a respectable newspaper at the time) reproduced the flyer as a lead-in to an article about how shameful it was that veterans couldn’t find decent paces to live. The article publicized our need, and my wife and I were offered this strange place to rent.

My darkroom was off a large kitchen. It was a makeshift arrangement. My light source cane from the ceiling fixture and I had to carry my prints through the kitchen into a small bathroom. Very often, although I had a full-time job during the day, my work in the darkroom lasted until one or two o’clock in the morning.

About the third week into the course, Grossman recommended that I purchase a used Checkoslovak 2½ x 3¼ enlarger. I was fortunate to find one. My enthusiasm about photography soared. I quickly outgrew my folding camera. One day, Sid showed me a 2½ x 2¼ Voitlander Brilliant camera. I saw how much easier it was to operate and the superiority of its viewing system. I wished I could afford a Rollieflex, but chose a Kodak Reflect instead. It was not as well made as the European models—the two front lenses came off the body as I focused on my subject—but the taking lens was excellent. Now I began to make the kind of photographs that I was passionate about. I brought these prints, dry mounted on small, white sheets of heavy paper, to class.

Because of my contact printing, I was able to use the enlarger to make prints that had the quality that I looked for in the contacts. Sid liked my work. Very often he used it in class to demonstrate a point he was making. None of the other students were photographing the kind of street scenes I was taking; few showed the technical skill I managed to achieve by my determination.

One Saturday morning it was snowing as I left the subway, on my way to the class. The wind howled through the city streets. People bent low to protect themselves against the wind-swept snow, as they tried to walk against it. With my back to the wind, leaning against a building to steady my hands, I opened my bellows camera and made two exposures. During the following week, the film was developed and I made a contact print for the class. When Grossman saw the print he stared at it for some time. He looked at me with one of his rare smiles and turned to the class. Holding up the print, he said, “This is what photography is all about.”

Several years later, I showed an enlargement of the print, entitled Snow Scene, to Edward Steichen, who was then the photography director of the Museum of Modern Art. He asked if he could keep the print on loan to the museum, along with two other photographs (one was a photograph of Byrant Park, that later become one of my best-known). I agreed. Several months later, the two prints, purchased by the museum for $5.00 each (from a “special fund”) were in a MOMA show called “Fifty-One American Photographers.” In 1976, I gifted the Snow Scene print to the museum, loaned so many years before, to commemorate the publication of my book, N. Jay Jaffee: Photographs 1947–1955. (Another copy of that print, in an 11×14 size, was shown as part of a C.W. Post College show in 1975, and sold for what was then the substantial sum of $100.)

Although I had been serious about photography before I entered Grossman’s class, I emerged from it convinced that this was the medium I should pursue. Sid’s aesthetic conceptions and ideas, along with his approval of my work, gave me the assurance that I could succeed. He validated my photographs. The images, in turn, validated me. The entire process—from taking the photograph to developing the negative to creating the print—felt entirely natural and instinctual.

Without realizing it, I picked up more than Sid Grossman’s philosophy of photography during those ten weeks. I also incorporated some of his belligerence and his mannerisms. In the early 1970s, I was asked to teach basic photography for adults at the North Shore Community Art Center on Long Island. I didn’t destroy any work—but I didn’t make too many friends, either. Nevertheless, several students insisted that I continue teaching privately. For the next three years, I lectured—aided by the spirit of Sid Grossman—to a group of eager, attentive listeners.

Recently, I had the opportunity to teach basic photography as an adjunct professor at C.W. Post College. It was a wonderful experience. I had mellowed since my earlier stint as a teacher. My students were younger and I gave them as much attention and encouragement as I could offer. Their appreciation for what I brought to them enhanced my own enjoyment of the class. I had the sense that I was returning a precious gift that Sid had given me.

I dedicated my book, in part, “to the memory of Sid Grossman, whose singular vision allowed me to see the world for a second time.” He taught me, in a few weeks, some objective visual truths that have lasted a lifetime. Perhaps, if Sid had lived long enough, he would have also mellowed. Hopefully, he would have received the honor and respect for his brilliance and his work that he so justly deserves.

©1993 N. Jay Jaffee. All rights reserved.